Albuquerque's Tent City Ordeal

Story by Rick Nathanson of the Journal

Candy Sanchez is sweeping her “yard,” such as it is – a patch of dirt, still moist from the previous night’s snow that covered it – as well as her adjacent “home,” a small tent she shares with her disabled husband and pregnant sister.

Sanchez, 27, is a resident of what has become known as Tent City, a row of about 30 tents sitting on a narrow spit of land along First Street between Coal and Stover SW.

“I don’t like staying in the shelters,” she says. “I’ve had bad experiences there with bugs and people.”

Candy Sanchez hangs a wet blanket on a fence to dry on Thursday. Occupants of Tent City went to sleep the night before as freezing winds blew and snow fell. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Sanchez has stayed in the overnight winter shelter operating out of the old West Side jail, but that was more trouble than it was worth, she says.

“They get you up at 4 or 5 a.m. and drive you back Downtown by 6 a.m., so we wind up here out in the cold anyway. I might as well just stay in the tent and try to keep warm. It’s not that I prefer this, I just don’t know what else to do,” she says, her voice cracking and her eyes welling with tears.

As Albuquerque’s Tent City has swelled since it started this summer, so have complaints to police. Those living and doing business nearby report fighting, drug dealing, public drunkenness, prostitution, litter, and urination and defecation on neighboring properties.

Gilbert Montaño, the mayor’s chief of staff, said there have even been reports of human trafficking of drugged and unconscious women. Law enforcement officials have been investigating.

And beginning this week, the city will conduct a two-pronged sweep of the camp, with police officers removing those involved in criminal activity, while representatives of social service agencies and shelter operators offer to connect the homeless with a host of services and options, he said.

Unfortunately, there may not be that many takers.

The occupants of Tent City are a mixed bag and a tough crowd. Some say they simply value their independence and want to be left alone. Others claim to mistrust shelters, having been assaulted or threatened while there, or having had personal items stolen from them. A few say they resent sitting through prayers and religious services before getting a meal or a bed.

And more than a few freely admit that their use of alcohol or drugs has prevented them from entry, or has gotten them barred from shelters and meal sites.

“I got thrown out of the Rescue Mission,” says Ray Jones, 44. “They said I can’t drink there. That’s who I am. That’s all I do. I’m an alcoholic and I smoke cigarettes by the pack.”

Jones says he has been drinking steadily since getting out of prison in September, where he served 17 years for attempted murder and other crimes. Drinking, he says, settles him down so he stays out of trouble. He wants to keep it that way.

“I know I’m never going back to prison,” he says. “I’ve been institutionalized, and in a way I am still institutionalized.”

Now, however, his prison is alcohol, he says, “but it’s my choice this time.”

A couple has a brief moment of tenderness as they warm themselves in the sun in front of a tent that serves as their home. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Modest start

Tent City started modestly enough last summer with a few people spending nights in tents they pitched along Iron Street, diagonally across from the Albuquerque Rescue Mission at Iron and Second SW, says pastor Rene Palacios, executive director of the mission. The mission also operates the overnight November-March winter shelter at the old West Side jail.

In June, the driver of a pickup truck veered onto the sidewalk, possibly on purpose, according to police. One woman was killed and several other homeless people injured.

No longer feeling safe at that location, the campers moved east on Iron, setting up their encampments along First Street, just in front of the tall chain link and barbed wire fence that separates a thin swath of earth from the railroad yard behind it.

Most homeless people “want to be in permanent, affordable housing and want help and access to social services,” Palacios says. “But for some, nothing seems to work, and they will just stay outside of all the systems. But they are the exceptions.”

Tent City is full of those exceptions. Living in tents is probably “not doing more harm than good,” but neither is it “the solution,” he says.

Organizations that place chronically homeless people into housing and plug them into support services have found that it can be less expensive than allowing these individuals to remain on the streets, drifting in and out of shelters, using hospital emergency rooms when they become ill and often winding up in jail, Palacios says.

A few cities, like Las Cruces, have a city-sanctioned tent city, where social workers have access to the occupants and the tent city residents police themselves. While they have more freedom than at many shelters, no drugs or alcohol is allowed.

In those situations, a tent city can be seen as a transitional step to more permanent housing, Palacios says.

Not so for Albuquerque’s loosely knit assembly of campers.

“There is no real self-government and no municipal law or codes to provide structure,” he says. “While it could be transitional for some, it’s not likely to be so for most.”

Courtney Bell, who manages and lives in the Orpheum Arts Space, locks a gate at the perimeter of her lot, located a “stone’s throw” from Tent City. Bell pushed the city to provide portable toilets for the campers, so they would stop using the property around her building as a bathroom. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Out of control

Courtney Bell manages and lives in the historic Orpheum Arts Space, “a stone’s throw” from the growing Tent City. The Orpheum has about 20 apartments for artists, eight art studios, a large performance space and some private businesses.

She is sympathetic to the plight of the homeless, but she says the situation has gotten out of control. She recalls one evening while out walking, her dog was “chased into the street by a screaming man” from one of the tents. Another time, a friend was walking his dog when both he and the dog were attacked by a homeless person’s unleashed animal, resulting in sizeable veterinary and urgent care bills.

Residents of the Tent City have trespassed onto her property, leaving behind duffel bags, razors and blankets, as well as needles and syringes. The alleyway bordering the south side of her property was nicknamed “Bathroom Alley” by area police officers because of the numerous piles of human feces, she says.

That became an even bigger biohazard after it rained and the fecal-contaminated water ran onto her property, she says.

Bell began “incessantly” writing letters and emails to her city councilor, Isaac Benton, as well as other city officials, outlining the problems and dangers presented by the homeless tent occupants, says Bell’s lawyer and former Orpheum resident James Llewellyn Dodd.

Benton was able to get the city to provide two portable toilets at Tent City. The sanitation problem has since improved, but Bell and other area residents are still pushing to have full-time security stationed at the site, Dodd says.

Benton also confirms the reports of noise, drug dealing, prostitution and other problems and says he has driven to the site and witnessed some of that activity.

“There is no easy answer,” he says, noting that, according to city officials, there is an ordinance prohibiting access and obstruction of movement along a city sidewalk or right of way, but no law specifically preventing people from camping there.

“I have sponsored legislation to attack the problems of mental illness and substance abuse” pervasive among the homeless, “and I am working on legislation and funding for housing and support services,” Benton says. “I want to see these people in supportive housing and for there to be case management, but you can’t force them into these things.”

NPPA First place in spot news!

Last August we had some crazy weather here in Albuquerque. It seemed everywhere I went there was some weather related story as it happened one amazing Friday evening when it rained so hard in such a short amount of time near downtown that it made for some dramatic images including the following of a man hanging on to a trash can to keep from being washed away as he looked at a flash flood headed his way. I've attached a short video I shot as well to give you a sense of how powerful the downpour was. The second photo was of a homeless man who was caught in another flash flood as he slept in a dry city arroyo but was quickly washed away with the massive current flowing downwards after heavy rains fell in the foothills. Luckily for him a witness managed to see him get swept away and called 911. I've also attached a shaky video to give you an idea of how he was saved by rescue personnel from Albuquerque's Fire Department who are trained in such types of rescue. NPPA chose these photos as first place for spot news in region no.8.

Elementary School put on Lockdown

APD officers respond to a possible active shooter near the Air Force Base forcing a local elementary school to go on lockdown.

From church to battleground

Jose Maria Perea, leader of a group of Penitente brothers, inspects a South Valley church that has become the focus of a legal fight between the Penitentes and the nonprofit Atrisco Heritage Foundation. Behind him is one of several statues located on the church grounds. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Linda Ortega chose to buy a house next door to a centuries-old South Valley church that she once considered her spiritual home.

Two syringes and latex gloves litter the base of a wall of San Jose Church. South Valley residents say intruders scale the fences, sometimes leaving graffiti and evidence of drug use.

San Jose Church sprang to life during the Christmas season, on certain feast days, and especially during Lent, when as many as 100 people crowded into the tiny church, Ortega recalled.

But the church at 2100 La Vega SW has remained silent since early 2013 when it was closed by the nonprofit that owns the property.

“They locked the gates and removed everything, including the bell of the church,” she said. “It was quite abrupt. It was shocking.”

Before the church was closed, a group of Penitente brothers say they opened the church regularly for religious services and welcomed the community to attend.

Today, the nonprofit that owns the property bars the Penitentes and plans eventually to reopen the church as a venue for public events other than religious services.

The church’s contents – including pews, life-sized santos carved from cottonwood, and even a wood-burning stove – were removed, people familiar with the church said.

Fences that surround the three-acre property do little to stop trespassers, Ortega said.

“Sadly, the property has been vandalized with graffiti, trash – lots of unsavory things going on behind the church,” she said.

The property recently showed evidence of visits by drug users, who left used syringes and other paraphernalia near a rear wall of the church.

The property today is fenced and locked while the legal dispute simmers between a group of Penitente brothers, who claim the church as their heritage, and the Atrisco Heritage Foundation, which has owned the property since 2006.

San Jose Church, a centuries-old South Valley church, was closed in early 2013, barring Jose Maria Perea and others from performing religious services there. The church’s contents, including carved santos and the church bell, remain in storage.

The Sociedad de Nuestro Padre Jesus, a group of Penitente brothers, filed a lawsuit last year in state District Court against the foundation, challenging the nonprofit’s legal right to bar Penitente brothers from the church.

The Penitente Brotherhood is a lay fraternity of Catholics that provided spiritual leadership for centuries in New Mexico and southern Colorado.

Even San Jose’s name is the subject of dispute. Court records refer to it as San Jose Church, but Penitentes call it the Morada de San Jose – the Spanish word for a Penitente church.

A spokesman for the Atrisco Heritage Foundation called it a Catholic church that for centuries was owned in common by heirs of the Atrisco Land Grant, who settled in the area more than 300 years ago.

Archbishop of Santa Fe Michael Sheehan called it a “chapel,” long used by Catholics as a place of worship. But the Roman Catholic Church does not own the property and has no stake in the outcome of the legal dispute, he said.

Eager to renovate

Peter Sanchez, executive director of the Atrisco Heritage Foundation, said the nonprofit is eager to renovate the church and open it to “the entire community” rather than a small group of Penitente brothers.

Jerome Padilla, president of the town of Atrisco board of trustees, stands in front of San Jose Church. Padilla and others want the church to be reserved for religious purposes.

“Their argument is that five or six people should be able to use this church exclusively,” Sanchez said of the Penitentes, whom he called “tenants” of the church in recent decades.

“Our argument is that the community should be able to use this church. When we say the community, we mean the whole community.”

Sanchez contends that the Penitentes controlled access to the church and largely closed it to the broader community. Sanchez also contends the church is in good condition and that the foundation is maintaining the property.

Ortega and others reject the contention that the church was closed.

“It was open to the community as it was,” she said. “Anybody could come and participate, or just observe, if they didn’t want to participate in the prayers.”

The Atrisco Heritage Foundation was formed in 2006 by the now-defunct Westland Development Corp. to preserve cultural properties, including San Jose Church and three cemeteries. Westland was the successor to the Atrisco Land Grant.

A key issue in the lawsuit is the validity of a 50-year lease that Westland granted to the Penitente brotherhood in 2006, giving it use of the church, according to the lawsuit. The Atrisco Heritage Foundation in its response denied that the Penitentes have a legal lease with Westland.

Sanchez said the nonprofit intends to restore the church and develop the property into an asset the community can use for a wide variety of events.

The foundation is working with a group of University of New Mexico graduate business students “to develop a strategic plan and feasibility study to develop the property in a way that is more beneficial to the community,” Sanchez said.

He said the project is modeled on the Old San Ysidro Church, which is owned by the village of Corrales and leased for events ranging from weddings to performances, but not as a church.

The foundation also wants to register San Jose Church on the National Register of Historic Places, he said. The designation makes owners eligible for investment tax credits to pay for rehabilitation of historic structures.

Religious artifacts removed from the church “are stored safely under our control,” Sanchez said. The foundation would not oppose handing the artifacts over to the Penitentes if a judge determines the rightful owners.

“We simply want the courts to decide,” he said.

Trespassing incident

Tension between the Penitentes and the Atrisco Heritage Foundation led to a confrontation Oct. 4 when foundation board members opened the gate to allow UNM students to view the church and a Penitente leader tried to enter the property, according to a Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Office report.

The conflict began when Jose Maria Perea, a spiritual leader of the Penitente group, drove his motorized wheelchair through the open gate when board members ordered him to leave, according to the report. Perea told a deputy that board members grabbed him and his wheelchair in an attempt to force him off the property.

Sanchez said of the incident that Perea was “trespassing onto our property, trying to disrupt a meeting between our organization and UNM. We had to call the police and have him escorted off.”

Neither Perea nor the board members sought criminal charges.

Perea, Ortega and other South Valley residents say they oppose the foundation’s plans to use the church for nonreligious purposes, such as community events.

San Jose is among the oldest churches in the region and should be used exclusively as a church, said Jerome Padilla, president of the board of directors of the town of Atrisco grant, a political jurisdiction composed of Atrisco heirs.

“We want to protect the traditional practices on that land,” he said.

Perea called the church a “cultural sanctuary” that for decades served both the Penitente brothers and the larger community.

Generations of Penitente brothers are buried there, both on the grounds of the church and under the church’s floor boards, Perea said during a recent visit to the church. Many of the graves are unmarked, he said.

“Every inch that you dig under this, there are bones of our ancestors,” he said.

Picture perfect: Photographers flock to refuge

Gary Chappel is bundled up tight against the cold. Despite the hooded parka, the skin surrounding his bearded face is pink and his nose is red.

It is 6 a.m. this weekday morning at the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge, south of Socorro, and the 60-year-old physician from Winter Haven, Fla., is patiently waiting for sunrise. His gloved hands hold a rather large camera, while another with an enormous lens is mounted on a tripod.

Just after 6:30 a.m., the horizon to the east begins to illuminate. The soft but constant chatter from ducks, snow geese and sandhill cranes gets progressively louder as the sky turns shades of amber, red and purple.

Florida physician Gary Chappel bundles up against the early morning cold at Bosque del Apache, waiting for just the right moment to take photographs. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

With a sudden thunderous flapping of wings, tens of thousands of birds become airborne in the first wave of a morning flyout.

Chappel presses the shutters on his cameras, capturing moments in time that will never be repeated in exactly the same way.

He is not alone. To his left and his right, lined up along a dirt road that runs adjacent to a large wetland area, are other people outfitted with camera gear. They, too, awoke early in the morning darkness and cold to see, hear and photograph the wintering water fowl in their stunning natural habitat.

As things settle down, Chappel reviews some of his shots on the preview screens of his cameras. He stops at a photo of birds, frozen in various poses of flight, juxtaposed against a fiery sunrise.

Crane celebrations

The 27th annual Festival of the Cranes will be held Tuesday through next Sunday at the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge south of Socorro.

Among the 142 events scheduled are tours, lectures and workshops on identifying birds, bird behaviors, and photographing and videotaping of birds.

Some of the events are free, though many require a fee and have limited space.

For a description of events and details, go to festivalofthecranes.com.

Today in Albuquerque, the Return of the Sandhill Crane Celebration takes place with free events scheduled from 9 a.m. through 3 p.m. at the Open Space Visitor Center, 6500 Coors NW.

Events include walking tours, bird displays, lectures and live music.

Call 897-8831 for more information or visit cabq.gov/openspace/visitorcenter.html.

“Wow! This is why I do this,” he says, exhaling cloudy wisps of moisture into the cold morning air. “Photography is really an excuse to come here. How else would I ever get to see something like this? There’s nothing like this in Florida. I’m a radiologist, so I look at pictures of people all day. This is much prettier and less depressing.”

Established in 1939, the Bosque del Apache is located along the Rio Grande Corridor, “a main migratory flyway in North America,” says Sean Brophy, the assistant refuge manager. “We get a tremendous abundance and variety of birds, some using the refuge as a stopover during their annual migration, but also many thousands of others that stay here through the winter.”

The refuge is 57,331 acres, of which 10,000 are managed as wetlands, Brophy says. In all, more than 530 species of birds can be seen throughout the year in addition to more common four-legged critters, including mule deer, coyotes, javelina, raccoon, beavers, bobcats and the occasional mountain lion and black bear.

Photography hobbyist Raybel Robles, 28, a resident of Grand Cayman Island in the Caribbean, was in the right place at the right time when he unexpectedly photographed a coyote stalking and setting its jaws into a snow goose.

An accountant assistant, Robles said he and his girlfriend, also a hobby photographer, planned their visit around a trip to the Bosque del Apache.

“I heard about it in an online forum for people who photograph birds, which is my main subject,” he says. “Finding different birds to photograph is very challenging but also very rewarding when you get a great shot. If it was easy, you’d get bored quickly.”

Larry Kimball, a professional photographer from Colorado, says the Bosque del Apache is “not like anything you can see anyplace else.” (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Robles, who was in his third day visiting the refuge, says his most lasting impressions are “images of the birds with the mountains in the background, and the beautiful light.”

Larry Kimball and his wife, Barbara Magnuson, both professional photographers from Cotopaxi, Colo., have visited the Bosque del Apache about a half-dozen times in the last decade.

“It’s spectacular. It’s not like anything you can see anyplace else – the sheer number of birds, the colors, the killer sunrises,” says Kimball, 67.

“I love coming down here, particularly at this time of the year with the autumn colors,” says Magnuson, 62. “It’s different each time we come, and we don’t know what to expect. Last year, we saw coyotes lying in the grass waiting for some snow geese. The birds, the wildlife, scenery, colors – there are just so many options and potential subjects.”

Mike Cohen

Mike Cohen, 64, a retired attorney from Lighthouse Point, Fla., has been visiting the Bosque del Apache every day for nearly two weeks. He parks his camper van at a nearby RV park.

Although mainly interested in the sandhill cranes, the numbers of other bird species make the entire spectacle “kind of overwhelming and magnificent.”

Cohen was waiting along a field where a couple of thousand snow geese were feeding in the grass.

“It’s exciting when in a sudden burst they all take off at once,” he said. “I’ve got one camera set up with a fast shutter speed to capture action all in focus, and one camera with a slow shutter speed and a neutral density filter to purposely blur the shot, making it more artistic.”

For Phoenix resident Gerry Vandaele, 73, photographing the birds and wildlife at the refuge is his way of sending the message that nature is important and to see it now, while it’s still here.

“I worry that the wildlife will disappear and we won’t be able to see it anymore,” said the retired phone systems engineer. “I’m trying to capture the moment because, you never know, it may not come again. Different species are becoming extinct all over the world. I worry about that for my grandchildren.”

A Great Horned Owl

“I love coming down here, particularly at this time of the year with the autumn colors,” says Barbara Magnuson of Colorado.

Photography hobbyist Raybel Robles, 28, a resident of Grand Cayman Island in the Caribbean, was in the right place at the right time when he unexpectedly photographed a coyote stalking and setting its jaws into a snow goose.

End of the line for Chino’s storied union

BAYARD – The southern New Mexico mining town of Santa Rita no longer exists, even as a ghost town, except in the memories of Terry Humble and others who lived there.

The ground beneath Santa Rita has been blasted, shoveled and trucked away over the last century to feed the world’s demand for copper, leaving a hole a mile-and-a-half wide and 1,500 feet deep.

In September, another vestige of Santa Rita disappeared when workers at the Chino Mine voted 236-83 to decertify a 72-year-old union celebrated for its heroic struggle to improve the lives of Hispanic miners and immortalized by the 1954 movie “Salt of the Earth.”

The Chino Mine, located about 12 miles east of Silver City, is among the world’s largest open-pit mines and still growing. Endless lines of huge Caterpillar trucks, each hauling 300 tons of copper ore and waste rock, grind slowly up steep inclines day and night. Some 960 workers continue to expand the massive hole.

All around are mountains of waste piles that dwarf many of the taller peaks in this rugged area.

When Humble, 73, returned to Santa Rita in 1963 after a hitch in the Navy, he realized that he needed to begin collecting photos and other evidence of his hometown before the growing pit swallowed it completely.

“That’s when I realized that Santa Rita was disappearing,” he said. “Better get what I could.”

Today, Humble and others are mourning the end of the labor union he joined in 1967 when he began work as a mechanic at the Chino Mine.

The Sept. 18 union election ended one of the nation’s most storied unions, the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers Local 890, commonly called Mine Mill Local 890.

The National Labor Relations Board certified the election results Sept. 30.

The union’s supporters say the move reflects a generational change by young miners who didn’t live through the struggles faced by their predecessors.

Improved mine safety and better wages played a role in declining union membership, said Humble, who co-authored a book, “Santa Rita del Cobre,” about the town and the mine.

In 1970, wages at Chino ranged from $24 a day for laborers to $32 a day for machinists, he said.

Hourly wages today at the Chino Mine range from $12.35 an hour for laborers to $23.20 an hour for a top mechanic, according to a three-year United Steelworkers contract negotiated in 2011. Wages are raised $1.50 an hour if copper prices exceed $2.75 a pound.

Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc., which owns the Chino Mine, issued this statement: “We believe that safe and productive mining operations can continue to be achieved in the workplace without a union at Chino, where employees are compensated fairly, treated with dignity and respect, and work as a team in a positive work environment.”

“If you’ve got a safe environment and a good wage, you don’t need a union,” Humble said. “Let’s hope it lasts.”

A 1916 photo of the Grant County mining town of Santa Rita, east of Silver City. By 1970, the town had vanished to make way for the expanding open-pit Chino Mine.

‘Can’t believe it’s over’

The Chino Mine, the town of Santa Rita and the union all are tightly braided in Humble’s memories.

“I can’t believe it’s over,” he said recently, sitting on a folding chair in the 1940s-era union hall in Bayard, where Local 890 members held often-raucous meetings for seven decades.

“I had a feeling the union would be decertified sooner or later. But I did not think it would be this soon and not by such a large margin. I was very, very disappointed.”

In this hall in 1950, Local 890 members voted to strike for better pay and working conditions at an underground mine north of Bayard owned by the Empire Zinc Co.

When a court injunction barred miners from manning the picket line, union members voted to allow women to continue the strike, over the strenuous objections of some miners.

The 15-month action in 1950-52, called the Salt of the Earth strike, forced Empire Zinc to grant better pay and working conditions for the mine’s Hispanic workers.

The strike was dramatized in the 1954 film “Salt of the Earth,” which was made by blacklisted filmmakers and cast with men and women who participated in the strike. The movie starred Juan Chacón, who served several terms as president of Local 890 from 1953-74.

“That really was our civil rights movement, both for Hispanic women and men,” said Frances Gonzales, 49, whose father participated in the strike.

Gonzales said she grew up around the union hall, where she attended meetings at her father’s side. Murals memorializing the Salt of the Earth strike line the hall inside and out.

Salt of the Earth, both the strike and the movie, called attention to the dangerous and discriminatory conditions faced by Hispanic miners, both at the Chino Mine and the many underground mines that dotted the area.

“It helped us to cross that barrier, to be accepted by the Anglo people who lived here,” she said. “They started to realize that we were treated very badly and very differently. That’s when a lot of barriers, little by little, started going down.”

Local 890 led periodic strikes at the Chino Mine to put pressure on company leaders during contract talks, including a nine-month strike in 1967-68. Chacón often spoke for the union in news stories about the strikes.

Mine Mill Local 890 was largely a Hispanic union, said Humble, who was among a handful of Anglo members. For many years, Hispanics were barred from the mine’s craft unions and the more-desirable jobs they represented.

“There was a strong incentive for Hispanics to join Mine Mill,” he said. “It was a chance for them to have some solidarity and a voice.”

The election

On the eve of the Sept. 18 union election, union leaders felt confident that they could fend off decertification, as they had in five previous elections from 1993 to 2004.

In most cases, union members had voted nearly 2-to-1 to remain unionized. In 1998, for example, members voted 333-172 to reject decertification.

Union leaders went door-to-door, handing out fliers and reminding members of the union’s heroic past.

“We had done a lot of house visiting,” said Ray Teran, a 40-year employee of the Chino Mine and chairman of United Steelworkers Local 9424-3, the successor to Mine Mill Local 890.

“We had a lot of people from out of state to help with organizing and helping people understand the difference between union and non-union.”

The results of the election, and the nearly 3-to-1 rejection of the union, stunned supporters.

“It’s just kind of hard to stomach,” Teran, 61, said in an interview at the union hall, located about three miles west of the Chino Mine.

Generational changes in attitudes toward unions help explain the results, he said. Most voting members were in their 20s and 30s, he said. Teran was one of only a half-dozen members who had worked at the mine 30 years or more.

“It’s the generation,” he said. “They have no sense for unionization. They weren’t around for the struggles that their grandparents and parents went through. They don’t realize the sacrifices that took place to get to where we are.”

Dwindling membership over the years took a toll on the union, Humble said.

At least 10 unions flourished at Grant County’s two copper mines in 1967 when Humble started work as a mechanic at the Chino Mine.

One after another since 1991, members voted to decertify unions for machinists, carpenters, boilermakers and other trade groups, he said.

At the Tyrone Mine, a second Grant County copper mine owned by Freeport-McMoRan southwest of Silver City, all three unions were decertified in 1994.

Local 890 had a membership of 560 in 1996. Its successor union had a membership of 343 last month when it was decertified.

Grant County’s mining workforce and union membership have fluctuated with the ups and downs in copper prices.

Fatal blow

The Chino Mine’s closure in 2008-09 may have delivered the fatal blow to the union, Humble said.

In 2008, operations at Chino were curtailed and hundreds of miners laid off after copper prices dipped under $2 a pound. Union membership dwindled to just a couple of dozen while the mine was closed in 2008-09, he said.

Copper prices have since rebounded to just over $3 a pound. In October 2010, Freeport-McMoRan announced it was restarting mining operations in Grant County. Today, 960 work at Chino and 620 at Tyrone, the company said.

“Everybody that has been hired lately, in the last several years, are new hires – a lot of younger people who have no idea of the advantages or disadvantages of a union,” Humble said.

Many say money also played a role in the union’s defeat.

Teran and others contend that Freeport-McMoRan paid annual bonuses to workers at the non-union Tyrone Mine but not to Chino employees. Some miners believe they will get bonuses, and possibly pay raises, now that Chino is non-union, he said.

Freeport-McMoRan said in a written statement that the company does not publicly discuss employee compensation. The Journal left repeated telephone messages with Irving Shane Shores, who organized the petition that led to the decertification vote, but they were not returned.

Many area residents say they are relieved the mines have reopened, even if they may regret the death of the county’s last miners’ union.

“This area is lucky to have (the mines), otherwise there wouldn’t be an economy in this area,” said Esther Gil, a councilwoman in Hurley, where Chino copper was smelted until 2007.

Her husband belonged to a Chino Mine union until his retirement a decade ago.

“Younger people don’t feel the attachment to the unions or understand that unions served an important purpose in improving people’s lives,” she said.

Terry Humble, 73, walks past the union hall in Bayard, which is covered inside and out with murals memorializing the Salt of the Earth strike, which won gains for Hispanic miners at the Empire Zinc Co. mine north of Bayard. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Ray Teran, a 40-year veteran of the Chino Mine, hugs Frances Gonzales, whose father was a longtime miner and union member. Teran was chairman of United Steelworkers Local 9424-3, which was decertified after a union election last month. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

A 1916 photo of the Grant County mining town of Santa Rita, east of Silver City. By 1970, the town had vanished to make way for the expanding open-pit Chino Mine.

A view of the Chino Mine from N.M. 152 about 12 miles east of Silver City. The open-pit copper mine, among the world’s largest, is a mile-and-a-half wide and 1,500 feet deep. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

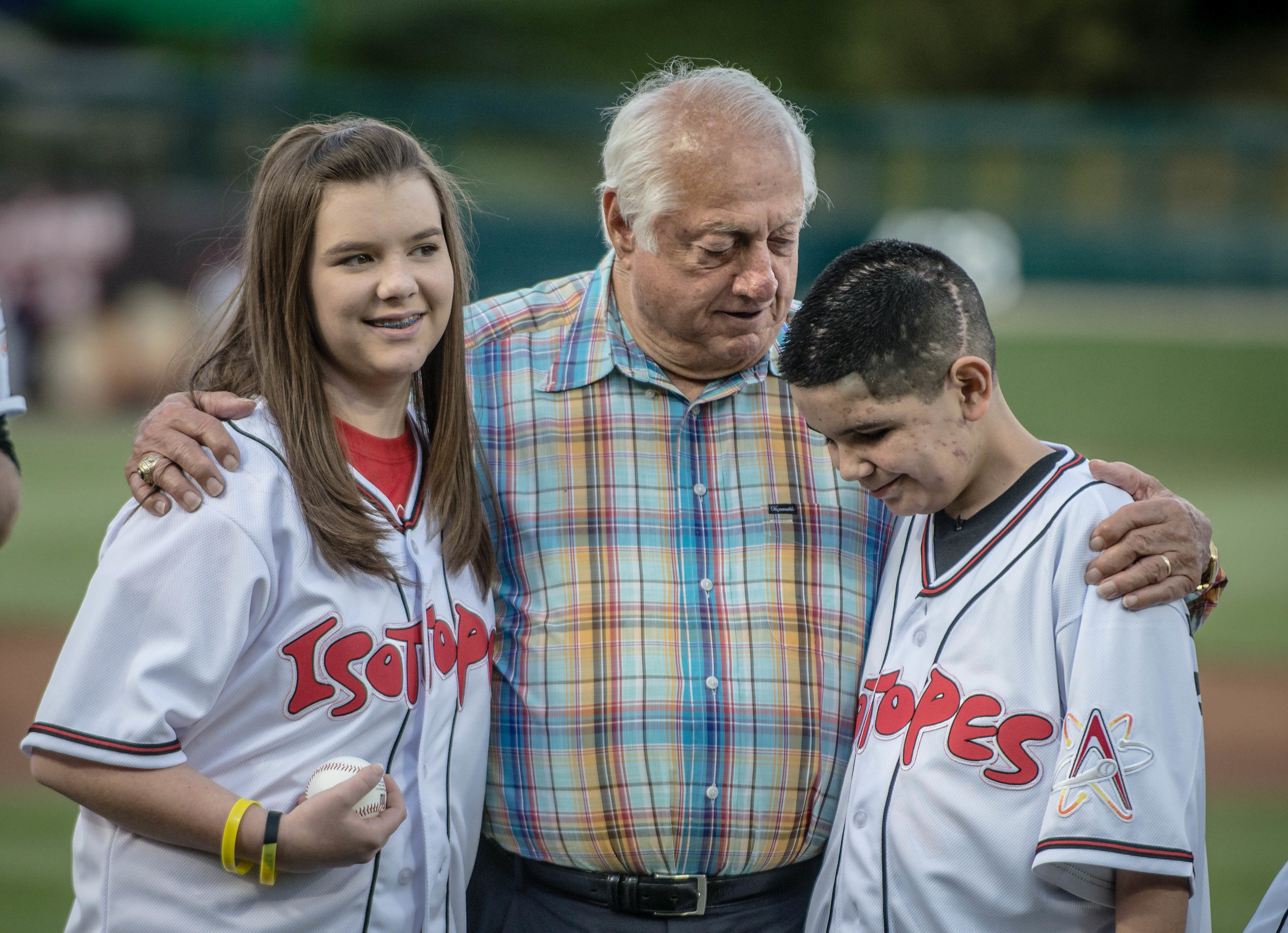

Jockeys visit Children's Hospital

A kid at UNM's Children's hospital gets a visit from local jockeys who brought gifts and smiles.

Last Week

This homeless man was swept away by a flash flood . Scenes like this one are common in the southwest around this time of year. The runoff from the Sandia mountains to the east of the city can carry a tremendous amount of water at fast speed, often catching kids playing in the nearby arroyos where it may appear dry some miles away.

This man was lucky to have survived due to the quick action of the citizens seen on the right who saw the him get swept away.

A news crew shot this photo of me as I stepped away from the scene.

Albuquerque Police officers as well as SWAT members rush a house to arrest a man who was believed to be brandishing a weapon in the southeast quadrant of the city.

Albuquerque Flash Flood

Record rain fell in Albuquerque in a matter of an hour.

Two drivers had to be rescued by Albuquerque firefighters when their car flooded in the downtown area.

The scene in downtown Albuquerque after record rain fell in an hour.

Teens bludgeoned homeless men to death

A woman picks wildflowers in the empty lot where two homeless men were attacked in their sleep and beaten to death – so badly they could not be recognized. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

A moment of silence is observed at the site where two homeless men were killed in west Albuquerque.

This woman along with a friend came across the bodies of the two men killed and called 911.

Gordon Yawakia, a prevention coordinator at the Albuquerque Indian Center, said both weekend murder victims, Allison Gorman and Kee Thompson, were clients and artists. Gorman was said to be a cousin of the late Navajo artist R.C. Gorman. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

A Native American man and his wife talk about their experiences of being assaulted on the streets of Albuquerque.

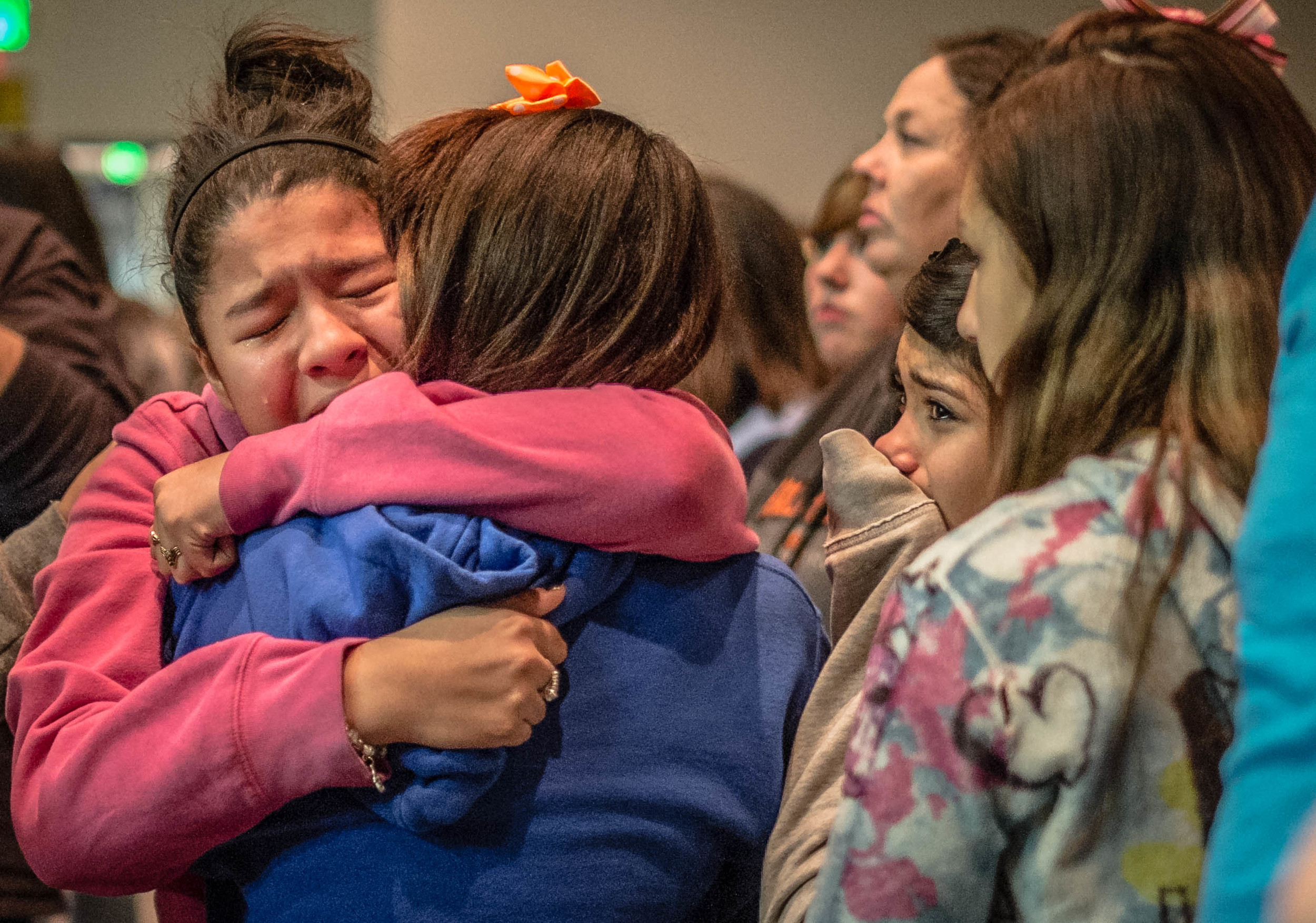

Family members of the teens accused react to hearing the bonds set at 5 million dollars.

Police said three Albuquerque teenagers took turns smashing cinder blocks on the heads of two sleeping homeless men, killing both in an attack so brutal that police haven’t been able to identify the victims.

And one of the teenagers told APD police the three friends have attacked dozens of homeless people at random throughout the city in the last year.

Alex Rios

Alex Rios, 18, Nathaniel Carrillo, 16, and Gilbert Tafoya, 15, were all arrested late Saturday on two open counts of murder and other charges, according to jail records.

Tafoya told police they have attacked as many as 50 homeless people in recent months, according to the criminal complaint, and police are asking possible victims to come forward.

The men’s bodies were found by a passerby at 8 a.m. Saturday in a field near 60th and Central.

“They are unrecognizable,” Simon Drobik, an Albuquerque Police Department spokesman, said of the victims. “My question is: Who failed these kids? How did it get to this point? It was so violent. I was sick to my stomach. Homicide (detectives) had a hard time dealing with it.”

Carrillo and Tafoya lived with their father at a home just north of the empty lot where the bodies were found, according to the complaint.

Nathaniel Carrillo

Police said the two men were asleep when the attack started. The teens also attacked a third man in the field, Jerome Eskeets, who had also been asleep but escaped and helped police identify the attackers, according to the complaint. He told police they wore black T-shirts over their faces as masks. As he ran, one of the teens yelled at him, Eskeets said, and that helped him recognize the youth as a nearby resident.

He also told police the teenagers had attacked several homeless people in the area in recent months.

Police found blood on Tafoya’s clothes and more blood on clothes found inside the home. Police also recovered a debit card and what may be the driver’s license of one of the deceased, according to the criminal complaint.

The three teens told police Tafoya and his girlfriend broke up and he was upset, so they went out late Friday night looking for people to beat up, according to the complaint.

In addition to the cinder blocks, the three young men also kicked and punched the two men and beat them with a metal pole and sticks, according to the complaint.

Gilbert Tafoya

“They went over there with the intent to hurt the individuals in this lot,” Drobik said at a news conference Sunday.

Drobik said all three teens are facing the same charges. Rios is being held at the Metropolitan Detention Center and Carrillo and Tafoya are at a juvenile detention center. Drobik said all three will likely be tried in adult court.

Richard Peralta, who lives east of where the beating happened, said several homeless people stay in the area and usually sleep and hang out in the field.

“The homeless people never bother us,” he said. “They are people and deserve the same respect as you, me or whoever.”

A man at Carrillo’s and Tafoya’s home on Sunday afternoon declined to comment.

Because Tafoya had boasted of attacking more than 50 homeless people, Drobik said police are asking any other possible victims to come forward.

“We’re are asking anybody in the social system who knows someone that expressed they have been attacked, that they reach out to those people to have them come to us and let us know what happened to them,” Drobik said. “We want justice for everyone.”

People with information can contact police at 242-COPS or call Crime Stoppers.

Drobik said police want to interview any homeless people attacked by the suspects so they can determine if Rios, Carrillo or Tafoya had any connection to a homeless woman who police said was intentionally run over with a truck near Second Street and Iron on June 9.

“A small clue, maybe a description of a truck, could tie everything up,” Drobik said.

Remembering Nancy Meyers

Volunteers and the homeless come together to remember Nancy Meyers, a homeless woman who was run over while she slept on the sidewalk near a shelter.

investigators at the scene where a homeless woman was rundown by an unidentified driver while she slept.

Naturalization Ceremony

Sister from Uganda Aisha Wilging ,9, and Flavia Wilging, 11, become U.S. citizens in a ceremony held in Albuquerque

Hundreds give veterans a hero’s welcome at the Sunport

U.S. Marine Corps Sgt. Nicholas McCreary presents an American flag to Charlotte Clark of Albuquerque on Friday at the conclusion of an Honor Flight, during which 22 New Mexico World War II veterans returned from an all-expense-paid trip to visit the National World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. Clark’s husband, Arthur Clark, had signed up for the Honor Flight but passed away in April. She was also presented a framed photo of her husband in his World War II Marine uniform. (Roberto E. Rosales/Albuquerque Journal)

Protesters 13 arrested in City Hall sit-in

Protester Nora Anaya is taken to the downtown detention center after being arrested. Anaya's nephew was killed several years ago by APD. She chained herself to a structure near the mayor's office. (Roberto E. Rosales/Journal)

An Albuquerque Police officer runs up to the Mayor's office to arrest protesters.

By Dan McKay and Rosalie Rayburn / Journal Staff Writers

One woman chained herself to an art case.

Others strung up crime-scene tape and shouted that the police chief should be fired.

It all happened inside the mayor’s suite on the top floor of City Hall on Monday, triggering the cancellation of the City Council meeting scheduled to start two hours later, which was to include discussion on a variety of bills centered on the Albuquerque Police Department.

Mayor Richard Berry was out of town, but his top administrator, Rob Perry, watched and later confronted protesters as they continued their sit-in.

The demonstration ended with the arrests of 13 people charged with criminal trespassing, unlawful assembly and interfering with a public official or staff. One person, University of New Mexico assistant professor David Correia, was charged with a felony for allegedly pushing a member of the mayor’s security detail.

Police quickly cut the chains that protester Nora Tachias Anaya had looped around a display case.

“All we asked is to talk to the mayor,” she said just before officers cuffed her with plastic ties.

The confrontation came four days after an autopsy report revealed police had shot a homeless man in the back in March. The shooting of James Boyd, who struggled with mental illness, triggered protests throughout the spring after police released video of officers firing at Boyd after he appeared to have agreed to surrender.

“We want answers,” Mary Jobe, whose fiance was also fatally shot by police, said in an interview. “We’re tired of the mayor hiding from us.”

The sit-in lasted about 90 minutes and triggered a lockdown of City Hall.

City Council President Ken Sanchez issued a statement saying the council meeting was canceled. He said that because City Hall had been locked down, holding a meeting would violate state rules that guarantee people can watch public meetings. He said he also had safety concerns.

Gilbert Montaño, the mayor’s chief of staff, said he expected councilors to meet later this week or next to take up Monday’s agenda, which included a tax increase for mental health and homeless services and legislation to overhaul civilian oversight of APD.

Members of the Coalition Against Police Brutality and the Answer Coalition, among other groups, who were gathered outside at the entrance to City Hall blasted the mayor for not meeting with them.

“We need answers and the police chief and the mayor does not give them to us – they hide, they hire people to do their talking for them. Where was the mayor for eight days after James Boyd was shot? He couldn’t face anybody because he’s a coward,” said Mike Gomez, father of Alan Gomez, who was fatally shot by police.

Police shot Boyd during a standoff in the Sandia foothills on March 16. Berry was out of town for a few days, and his first publicly reported statement on the incident was on March 24.

It was the third disruption at City Hall in a month. In early May, protesters tried to serve a “people’s arrest warrant” on Police Chief Gorden Eden during a City Council meeting, and they took over the council chambers to hold their own meeting as the chief and city councilors left.

Protesters later held a silent demonstration during a council meeting. Several signed up to speak during the public comment portion of the meeting, then stood quietly when it was their turn to address the council. Security escorted them out.

Protesters and the mayoral administration offered different explanations for how Monday’s protest started.

Montaño said Correia pushed his way through the interior door as other people were going in. Correia “rammed through the door and pushed one of our officers,” Montaño said.

The mayor’s suite, on the 11th floor, features a public lobby, with two aides behind a counter to greet visitors. A glass door prevents people from entering the mayor’s suite of offices without permission. Usually, the aides will press a button to unlock the door when people arrive.

Inside the mayor’s suite is a complex of individual offices and conference rooms. The protesters held their sit-in amid a reception area just outside the mayor’s individual office, where he has his own desk and conference table.

Barbara Grothus, one of the people arrested, said protesters didn’t have to force their way into the mayor’s suite. “There was no lock,” she said. “We just opened the door and walked in.”

Montaño said Correia was charged with battery on a police officer. Correia has led other demonstrations at City Hall over the past month. He said some of the tactics are modeled on historic demonstrations by land-grant and Chicano activists. The university has issued statements saying Correia does not represent UNM.

Monday’s sit-in led to an odd scene. Perry, the mayor’s chief administrative officer; Montaño; and a few police officers watched as protesters read from letters they’d intended to deliver in person to Berry. At one point, protesters sat quietly on the floor and read from a U.S. Department of Justice report that found APD had a pattern or practice of violating people’s civil rights.

The door to Berry’s individual office was closed, and a security guard stood watch.

Perry engaged protesters and appeared to use his cellphone to film them. “Did you force your way through that door?” he asked at one point.

Later, he urged them to leave peacefully. “You’ve made your point,” he said. “Why don’t you take off?”

Protesters responded that they weren’t leaving until the mayor came out to talk to them.

Montaño, at one point, said Berry wasn’t present, though he didn’t mention that the mayor was out of town. It wasn’t clear whether the protesters heard Montaño or simply didn’t trust him. Several kept asking if the mayor was shut in his office or if he’d escaped out a back door.

A police van that took arrested protesters from City Hall to the Public Safety building was met with a small crowd shouting messages such as “no justice, no peace” and “killer cops.” A cordon of police made a barrier between them and the van as the arrestees were led in.

Afterward, Montaño said the mayor welcomed civil, productive comment from the community. Berry was in New York on Monday for a conference, he said. Montaño said the arrests came only after protesters made it clear they weren’t leaving unless forced.

Tibetan monks stop in Albuquerque

Tibetan monks continue work on a Mandela before performing at the University of New Meixco

Wells Blog

Duis mollis, est non commodo luctus, nisi erat porttitor ligula, eget lacinia odio sem nec elit. Maecenas faucibus mollis interdum. Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue.